Only about 30% patients require hospitalised care in a Dedicated Covid Hospital. But glitches in following protocol, a lag in reacting to changing patient requirements, and inadequate resource-monitoring is leading to inefficient utilisation of critical care beds and equipment.

With 17,671 cases and 655 deaths until May 15, Mumbai has the highest Covid-19 burden in the country. Every day, the city is adding close to 1,000 new Covid-19 cases — and racing far ahead of other Indian cities.

The pace of increase of infections has also changed dramatically. So, in the 51 days from March 11 to April 30, the city recorded 7,061 cases — but it has since raced to add over 10,000 cases in just the first 15 days of May.

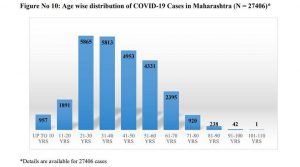

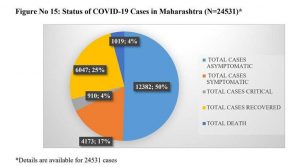

Maharashtra government statistics show that 27 per cent of Covid-19 infections are symptomatic, while 3 per cent of patients are critical and in need of immediate medical care. While this is only a small percentage of the total cases, the city still faces an acute shortage of hospital beds for these critical patients.

Here is a current situation report, and why this is happening.

Types of facilities available: CCCs, DCHCs, and DCHs

For ensure ease of managing patients, the available facilities are segregated into layers, based on what symptoms and health conditions a particular Covid-19 patient exhibits.

Lowest in the hierarchy is a Covid Care Centre (CCC). Among CCCs, there are two categories — the first, CCC-1, is meant to only quarantine people who are high-risk suspects, say, slum-dwellers who cannot practise social distancing at home.

The second category (CCC-2) is to admit asymptomatic positive cases, or cases with mild symptoms — such as those who are young with a history of fever, dry throat, etc., but who are stable at present.

Mumbai has 22,941 beds in CCC-1, and 34,329 beds in 241 CCC-2 facilities.

Next in the hierarchy are Dedicated Covid Health Centres (DCHCs), which admit moderately ill Covid patients. Patients with continued fever, cough, and cold will be admitted in these centres.

Senior citizens with slight fever will also find a place in these centres — as well as people with co-morbidities like diabetes, hypertension, heart ailments, and those with light symptoms. These categories of people will require a bed in these facilities since they remain at risk of falling severely ill.

There are roughly over 10,000 beds in DCHC.

At the top in the hierarchy are the Dedicated Covid Hospitals (DCH), which admit critically ill patients like those who require ICU or ventilator support, or patients who are gasping for breath.

The DCHs also admit some moderately ill patients — for example, a senior citizen who has low oxygen levels and a fever and remains at risk of further complications, will be kept here.

The are over 4,800 beds in DCH centres.

Nature of current challenges: gaps in following protocol

There is enough space to admit people in CCCs and DCHCs, but when it comes to DCHs, the beds are limited, there is a waiting period, and several patients die waiting for a bed.

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has directed its public hospitals to strictly follow protocol — if a patient in DCH gets stable and can be monitored in DCHC, the patient has to be immediately shifted to make space for other critical patients.

This process is currently slow, a real-time updating of beds is not happening, and private hospitals are not strictly following this protocol.

“While government hospitals are still following it, private hospitals continue to keep a patient admitted until he tests negative and can be discharged. He may remain admitted even if he is stable for days at length, although he should ideally be moved to a lower category,” an assistant commissioner in BMC’s South Mumbai ward said.

The official added that the BMC does not have the manpower to keep a watch on all private hospitals, and to constantly monitor the kinds of patients who are being admitted.

It came across instances where senior citizens who do not have any symptoms but have diabetes or hypertension are admitted in DCH, although they can be medically treated in DCHC.

A case-by-case decision has to be taken for each moderately ill patient on whether she requires treatment in DCH or DCHC. That is currently not happening for every patient.

Dr Hemant Deshmukh, Dean, KEM Hospital, said, “While protocol mandates to keep critical patients in DCH facilities, there are also patients, say those with renal failure or cancer, who are stable but can turn into severe cases anytime. We can’t move them out. It is a call that each treating doctor has to take.”

What the numbers show: mismatch between data and action

As per state government data, symptomatic and critical patients add up to 30 per cent of the total. Of the 17,671 Covid-19 cases confirmed until May 15, over 12,500 continue to be active — the rest have either recovered or died.

So, not more than 3,750 patients (30% of 12,500) require hospitalised care in a DCH. Mumbai has over 4,800 beds for this pool, and yet there is a shortage.

BMC officials said what remains the biggest challenge is to make hospitals update information, and to ensure that they follow a strict discharge policy so that beds are available quickly for new patients.

“At any given time, 95-97 per cent beds in DCH are full,” said Dr Daksha Shah, Executive Health Officer, BMC. “If a patient is discharged from a DCH, a hospital has to inform BMC’s disaster cell at 1916 which has real-time data on vacant and occupied beds, and directs patients to a hospital accordingly. That is not happening.”

Last week, Gokuldas Tejpal Hospital, a DCH facility, had three beds free for Covid-19 patients, but its online records showed the hospital was full. “That is because the concerned medical officer was not updating data in real time,” a doctor from the hospital said.

Tackling the situation: Solutions and the way forward

It is not possible to monitor every private hospital due to the sheer shortage of human resources at the BMC. The BMC is therefore, trying to increase capacity. There are plans are to add at least 3,300 beds in both government and private hospitals under DCH by May-end.

“Eighty per cent of the load is currently being handled by government hospitals,” said Manisha Mhaiskar, Officer on Special Duty in the BMC.

Maharashtra Health Minister Rajesh Tope has asked private hospitals to reserve 60 per cent beds for Covid-19 patients; this too, will boost capacity.

Simultaneously, BMC will provide intensive care units in CCC-2 facilities so that, if required, patients in need of oxygen support or some intensive treatment can be admitted there.

In Mulund, a school has 10 ICU beds in its CCC-2 facility. In NSCI Dome, Worli, 70 such beds are planned, and a few beds are planned in Goregaon’s NESCO and BKC grounds. Goregaon NESCO, BKC and Worli’s NSCI are all CCC-2 facilities.

“Currently in my ward there are 75 beds in CCC, and 28 are vacant. If there is oxygen support, more patients can be admitted here,” said Prashant Gaikwad, Assistant Commissioner, Ward D, in Mumbai.