The United Arab Emirates will despatch a satellite to Mars to study its weather and climate this week.

Hope, as the 1.3-tonne probe is called, is launching on an H-2A rocket from Japan’s remote Tanegashima spaceport.

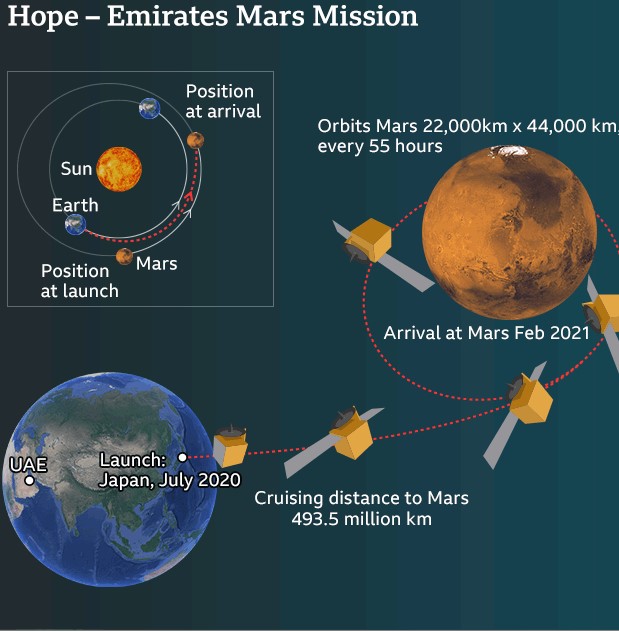

The 500-million-km journey should see the robotic craft arrive in February 2021 – in time for the 50th anniversary of the UAE’s formation.

Lift-off is scheduled for 05:43 local time on Friday (20:43 GMT; 21:43 BST on Thursday).

An earlier attempt on Wednesday was called off ahead of time because of expected poor weather conditions over Tanegashima.

Hope is one of three missions launching to Mars this month. The US and China both have surface rovers in the late stages of preparation.

Why is the UAE going to Mars?

The UAE has limited experience of designing and manufacturing spacecraft – and yet here it is attempting something only the US, Russia, Europe and India have succeeded in doing. But it speaks to the Emiratis’ ambition that they should dare to take on this challenge.

Their engineers, mentored by American experts, have produced a sophisticated probe in just six years – and when this satellite gets to Mars, it’s expected to deliver novel science, revealing fresh insights on the workings of the planet’s atmosphere.

In particular, scientists think it can add to our understanding of how Mars lost much of its air and with it a great deal of its water.

The Hope probe is regarded very much as a vehicle for inspiration – something that will attract more young people in the Emirates and across the Arab region to take up the sciences in school and in higher education.

The satellite is one of a number of projects the UAE government says signals its intention to move the country away from a dependence on oil and gas and towards a future based on a knowledge economy.

But as ever when it comes to Mars, the risks are high. A half of all missions sent to the Red Planet have ended in failure. Hope project director, Omran Sharif, recognises the dangers but insists his country is right to try.

“This is a research and development mission and, yes, failure is an option,” he told BBC News.

“However, failure to progress as a nation is not an option. And what matters the most here is the capacity and the capability that the UAE gained out of this mission, and the knowledge it brought into the country.”

Robotic probe: Hope has taken six years to develop

How has the UAE managed to do this?

The UAE government told the project team it couldn’t purchase the spacecraft from a big, foreign corporation; it had to build the satellite itself.

This meant going into partnership with American universities that had the necessary experience. Emirati and US engineers and scientists worked alongside each other to design and build the spacecraft systems and the three onboard instruments that will study the planet.

While much of the satellite’s fabrication occurred at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado, Boulder, considerable work was also undertaken at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) in Dubai.

LASP senior systems engineer Brett Landin believes the Emiratis are now in a great place to do another mission on their own.

“It’s one thing to tell somebody how to ride a bike but until you’ve done it, you don’t really understand what it’s like. Well, it’s the same with a spacecraft. I could give you the process for fuelling a spacecraft, but until you’ve put on an escape suit and transferred 800kg of highly volatile rocket fuel from storage tanks into the spacecraft, you don’t really know what it’s like.

“Their propulsion engineers have now done it and they know how to do it the next time they build a spacecraft.”

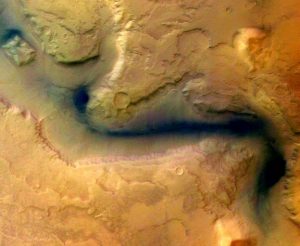

Surface features indicate Mars once had abundant flowing water

What science will Hope do at Mars?

The Emiratis didn’t want to do “me too” science; they didn’t want to turn up at the Red Planet and repeat measurements that had already been made by others. So they went to a US space agency (Nasa) advisory committee called the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) and asked what research a UAE probe could usefully add to the current state of knowledge.

MEPAG’s recommendations framed Hope’s objectives. In one line, the UAE satellite is going to study how energy moves through the atmosphere – from the top to the bottom, at all times of day, and through all the seasons of the year.

It will track features such as lofted dust which on Mars hugely influences the temperature of the atmosphere.

It will also look at what’s happening with the behaviour of neutral atoms of hydrogen and oxygen right at the top of the atmosphere. There’s a suspicion these atoms play a significant role in the ongoing erosion of Mars’ atmosphere by the energetic particles that stream away from the Sun.

This plays into the story of why the planet is now missing most of the water it clearly had early in its history.

To gather its observations, Hope will take up a near-equatorial orbit that stands off from the planet at a distance of 22,000km to 44,000km.

“The desire to see every piece of real estate at every time of day ended up making the orbit very large and elliptical,” explained core science team lead on Hope, David Brain from LASP.

“By making those choices, we will for example be able to hover over Olympus Mons (the largest volcano in the Solar System) as Olympus Mons moves through different times of day. And at other times, we’ll be letting Mars spin underneath us.

“We’ll get full disc images of Mars, but our camera has filters, so we’ll be doing science with those images – getting global views with different goggles on, if you like.”

Sarah Al Amiri is also a minister in the government

Who is Sarah Al Amiri?

The science lead on Hope is also the UAE minister of state for advanced sciences – and in many ways is the face of this mission.

She first got involved with the MBRSC as a software engineer and is now trying to spread her passion for space far and wide.

It’s notable that 34% of Emiratis working on Hope are women. “But more importantly, we have gender parity in the leadership team of this mission, across all deputy project manger roles reporting to Omran,” the minister said.