Cyclone Amphan has made violent landfall in eastern India and Bangladesh, lashing communities along the coast with ferocious wind and rain.

People rushed for shelter in Kolkata as the cyclone approached

It uprooted trees and toppled dwellings in both countries, including in the Indian city of Kolkata in West Bengal.

Nearly three million people were evacuated – most of them in Bangladesh – before the severe storm hit. At least five deaths have been reported.

Coronavirus restrictions have been hampering emergency and relief efforts.

Covid-19 and social-distancing measures have made mass evacuations more difficult for authorities, with shelters unable to be used to full capacity.

The storm, which was the first super cyclone to form in the Bay of Bengal since 1999, is expected to have caused deadly storm surges. Its winds have now weakened but it is still classified as a very severe cyclone.

“Our estimate is that some areas 10-15 kilometres from the coast could be inundated,” said Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, the head of India’s meteorological department

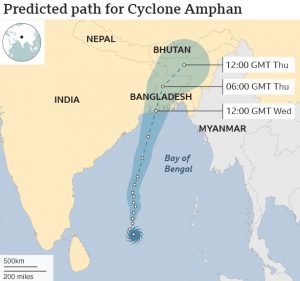

Amphan began hitting the Sundarbans, a mangrove area around the India-Bangladesh border home to four million people on Wednesday afternoon, before carving north and north-eastwards towards Kolkata, a historic city that was the capital of the British Raj.

It was moving with winds gusting up to 185km/h (115mph). Amphan is expected to move further into Bangladesh on Thursday, and later Bhutan.

Satya Narayan Pradhan, director general of India’s National Disaster Response Force, told the BBC it already looked like the impact had been “fairly devastating”, especially in poor areas.

He said reports were coming in of “a lot of fallen trees, fallen houses, uprooted telephone lines, electricity poles”.

Although it had been hard to keep people apart during evacuations, social distancing is being enforced at cyclone shelters, along with hygiene protocols, he said.

In Kolkata, residents said it was the worst storm they had experienced in decades. They spoke of flooded homes, electricity transformers exploding and power cuts. One man told the BBC the boundary walls of his condominium had collapsed.

“I am in my house. I have been prepared for a while. But I’ve never seen a storm as bad as this,” said one resident, Pooja Kaur. “There is no power at the moment.”

Earlier, a Bangladesh Red Crescent volunteer helping villagers to evacuate became the first fatality after the boat he was in capsized in strong winds, the organisation said.

Bangladesh has reported two other deaths – both caused by falling trees. In India, media reported two fatalities, including a child in the state of Orissa (also known as Odisha) who was killed after the mud wall of his family’s home collapsed.

In the Sundarbans, also a rich habitat for Bengal tigers, houses “look like they have been run over by a bulldozer”, a villager called Babul Mondal told the AFP news agency.

India and Bangladesh are using schools and other buildings as temporary shelters – but they need more space than usual in order to house people while maintaining social distancing.

Police in West Bengal, which along with Orissa is expected to be the worst-hit part of India, told the BBC that people were unwilling to go to the shelters because they were afraid of contracting Covid-19.

Officials in Bangladesh fear it will be the most powerful storm since Cyclone Sidr killed about 3,500 people in 2007. Most died as a result of sea water surging in.

India’s weather department had predicted storm surges as high as 10-16 feet (3-5 metres). The rising of sea levels in this way can send deadly walls of water barrelling far inland, devastating communities.

The cyclone comes as tens of thousands of migrant workers continue to flee cities for their villages during India’s lockdown to curb the spread of coronavirus. West Bengal and Orissa are among the Indian states seeing large numbers return.

Orissa cancelled trains and some district officials asked the state government to accommodate the migrants – many of whom are walking home – elsewhere until the storm passes.

Although they are not in the direct path of the storm, there are fears for hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees who fled Myanmar and live in crowded camps in Bangladesh where cases of coronavirus have recently been reported. Officials said they had moved hundreds of Rohingya living on an island in the Bay of Bengal into shelters.

The UN and human rights groups are also gravely worried for Rohingya refugees who they believe could be on boats in the Bay of Bengal, and possibly in the storm’s path, after trying to flee to Malaysia and Thailand but being blocked by authorities in those countries from landing.