Indonesia has plans to lift restrictions and embrace a “new normal” but the sharp spike of COVID-19 cases makes this look like bad timing, says Dr Deasy Simandjuntak.

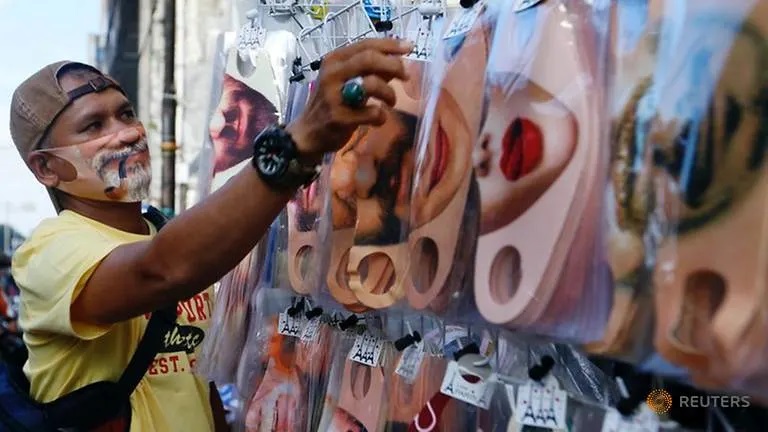

A vendor sells face masks at a traditional market in Jakarta, Indonesia, Jun 23, 2020.

SINGAPORE Indonesia became Southeast Asia’s worst-hit nation last week (Jun 17) when its COVID-19 cases surpassed 41,000.

The situation has since worsened as on the following day (Jun 18) Indonesia recorded 1,331 new cases – its highest since it first began counting daily cases in March.

How did Indonesia get to this bleak situation? The number of new cases has consistently been more than a 1,000 daily since Jun 12, with East Java and Jakarta as the worst-hit areas, though the daily came down slightly to 862 on Sunday (Jun 21).

However, as of Wednesday (Jun 24), Indonesia had surpassed more than 49,000 cases, with Jakarta and East Java accounting for almost a quarter each of those figures.

Indonesia also has the region’s highest number of deaths and active cases, which stood at 2,573 and 29,351, respectively on Wednesday.

While COVID-19 related fatality rates have been brought down from 8 per cent to 5.3 per cent, they are still the highest in Southeast Asia, which has an average death rate of 2.7 per cent according to Indonesian media Kompas.

WAS EXPANDED TESTING THE REASON?

One explanation for the spike of new cases is that Indonesia has ramped up its COVID-19 testing.

Up until May, the country conducted less than 500 tests per 1 million population – one of the lowest test rates in the world and the third lowest in the region.

Yet by last week, the country managed to quadruple that to 2,126 tests per 1 million population, even reaching the target of conducting 20,000 tests in a day.

Although the improved testing capacity is good news, the spike in daily cases reveals how severe the situation is.

According to the spokesperson of Indonesia’s COVID-19 task-force Achmad Yurianto, the government focuses on contact tracing tests and not on random tests.

FILE PHOTO: A healthcare worker wearing protective gear walks through a traditional market as swab samples are collected from vendors to be tested for the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in Jakarta, Indonesia, June 25, 2020.

However, people can voluntarily go to hospitals to get tested for reasons such as to fulfil the prerequisite for air travel, or upon returning from travel.

In the last month, some cities such as Jakarta and Bandung, have also initiated their own random tests, testing samples from market-goers, travellers and public clinic visitors, in addition to health workers.

This means that the current high number of cases have come from both contact-tracing and random tests and, as such, are a reflection of the dire situation on the ground.

The fluctuation and inconsistency in testing capacity is also a problem. Despite having tested 20,000 specimens last week, the country only managed to test around 11,000 specimens on Monday (Jun 22).

Lamenting this, Planning Minister Suharso Monoarfa said on Jun 22 that Indonesia should increase its testing capacity and aim for 30,000 tests per day.

IS INDONESIA READY TO LIFT RESTRICTIONS?

But the Indonesian government has found itself in an awkward position as, at the end of May, President Joko Widodo had declared that the country was ready to move towards a “new normal”: To reopen businesses and facilities and lift other restrictions put in place to limit the infection.

Jakarta, albeit recording more than 100 new cases daily, has eased its large-scale social restrictions and gradually allowed businesses to reopen, since Jun 8.

It has also resumed public transport to restart and for shopping malls and places of worship to open their doors, albeit with capacities halved and physical distancing imposed.

Unsurprisingly, as businesses and working from offices resume, workers have thronged the public transport stations over the last two weeks, causing long queues and crowd build-ups, rendering physical distancing utterly impossible.

At first glance, Indonesia’s actions do not seem out of sync with wider trends across Southeast Asia, where countries are gradually reopening economies after flattening their infection rates given months of lockdowns and other stringent coronavirus restrictions.

Malaysia has done so in stages after nearly three months of a strictly imposed movement control order (MCO).

Singapore has just transitioned into Phase 2 of its reopening, allowing dining-in, retail and social activities with five or fewer people.

Thailand has managed to attain zero local cases for over 20 days and is considering allowing inbound travel for business visitors.

Yet Indonesia is lifting bans while it is recording four-digit new cases daily.

Having snubbed health experts’ suggestions to apply strict restrictions, and after a long period of dithering, the country only began introducing the loose restrictions on the last day of March.

Worse yet, policy flip-flops, such as banning but later allowing motorcycle taxis to carry human passengers after protests, or inconsistencies, such as banning people from returning to their hometowns for Hari Raya festivals – known as mudik – yet allowing work-related travel, as well as weak enforcement of social restrictions have marred implementation.

FILE PHOTO: Passengers are seen wearing a protective face mask at a Sudirman train station as the government eases restrictions amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Jakarta, Indonesia, June 8, 2020.

These factors became calamitous when combined with overwhelmed healthcare facilities in some places and a long period of an extremely low testing rate.

Although Jakarta hospitals now seem able to manage the surge of patients, at the end of May some hospitals in Surabaya, the country’s second largest city, were reported to be so overwhelmed by new cases that they were forced to turn patients away.

Large hospitals are now limiting patients and procedures, including planning to build separate access to prevent cross-infection, but smaller hospitals might not have the capacity to do so. This means that they would still be overwhelmed if there is an upsurge caused by looser restrictions in this “new normal”.

Yet the economic fallout of the pandemic is also looming large.

The country’s 2020 national budget deficit is predicted to reach more than 6 per cent – one reason why proponents of the “new normal” approach have urged and supported the government’s move to open nine critical economic sectors, namely mining, oil, industry, construction, estate crops, agriculture and livestock, fisheries, logistics and goods transportation.

In an interview on Jun 1, the Coordinating Minister of Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto highlighted businesses must resume to limit layoffs. He also mentioned that the government would create 89 new projects that would absorb 19 million workers in the next five years.

Over 1.75 million workers had lost their jobs by May, according to the Labour Ministry. A total of 4 million to 5.5 million people are projected to lose their jobs this year, Planning Minister Suharso Monoarfa said on Monday (Jun 22).

The Indonesian Chamber of Commerce’s data indicates that the job losses thus far due to COVID-19 is even higher at 6.4 million people as economic activities have been reduced by 30 per cent.

BUT BUSINESSES ARE PUSHING TO RESTART

The trouble is consumption-driven Indonesia knows it is highly dependent on physical activities resuming to kick-start the economy.

Economists have reiterated that COVID-19 restrictions have reduced Jakarta’s mall revenues by up to 90 per cent.

Businesses, sensing this, have been quick to defend the policy to boost consumer spending.

The Vice Chairman of the Indonesian Business Association Shinta Kamdani has also said on Jun 2 that prolonged restrictions on business activities would result in mass layoffs as businesses can no longer afford to pay their employees.

Similarly, the Chairman of the Indonesian Retail Business Association Roy N Mandey claimed the opening of retail businesses “can turn the [national] economic wheels”.

Meanwhile questions regarding public health begin to stew beneath the surface. Criticising the easing of restrictions, public health experts have expressed deep concerns.

A worker sprays disinfectant in a shopping mall, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, in Tangerang, near Jakarta, Indonesia, March 12, 2020 in this photo taken by Antara Foto March 12, 2020.

Pandu Riono, University of Indonesia’s leading epidemiologist, recently warned in The Washington Post that the prioritising of business interests amid a brewing of public health crisis could bring on a second wave of infections when Indonesia was far from a “new normal”.

Critics have highlighted the discrepancy between the greater attention given to the reopening of the economy and the considerably less attention given to the public health crisis.

NOT YET EXPERIENCED A PEAK

Epidemiologists have highlighted that Indonesia has not even reached its pandemic peak, which makes the “new normal” campaign not only premature but also counterproductive at a crucial time when stemming the spread must be priority to prevent an explosion of infections.

They believe such an announcement could lead many Indonesians to be complacent and less vigilant in following COVID-19 protocols.

A survey done by researchers of the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance, the Bandung Institute of Technology and the Indonesian Islamic University shows that social restrictions were effective in limiting people’s movement, hence limiting the virus spread.

Instead of urging people to go out, the Indonesian government should have intensified restrictions for a longer period before gradually opening businesses.

KEEPING ECONOMY OPEN WON’T ENCOURAGE SPENDING

The currently high COVID-19 infection rates actually deter people from spending money as the health risks may deter them from going out much and they may also opt to save in anticipation of income uncertainties, thus negating the intended economic results of the easing of restrictions in this period.

If infection rates continue to escalate due to the easing of restrictions, the government would have to once again slap on social restrictions and constrain economic activities, with an open-and-shut dynamic pushing the Indonesian economy towards the brink of recession, compared to tackling the pandemic head on in an early stage of Indonesia’s coronavirus fight.

Indonesia seems to be caught between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, the economy needs to be revived, while on the other, the soaring number of daily cases and high fatality rate beg for more stringent mitigation policies.

Ramping up tests and increasing public knowledge including promoting strict safe distancing, frequent hand-washing and correct usage of face masks must be prioritised amid the reopening of the economy.